I’m Still Invisible: A Week in San Francisco and Realizing Asexuality is One of the Queerest Things You Can Do

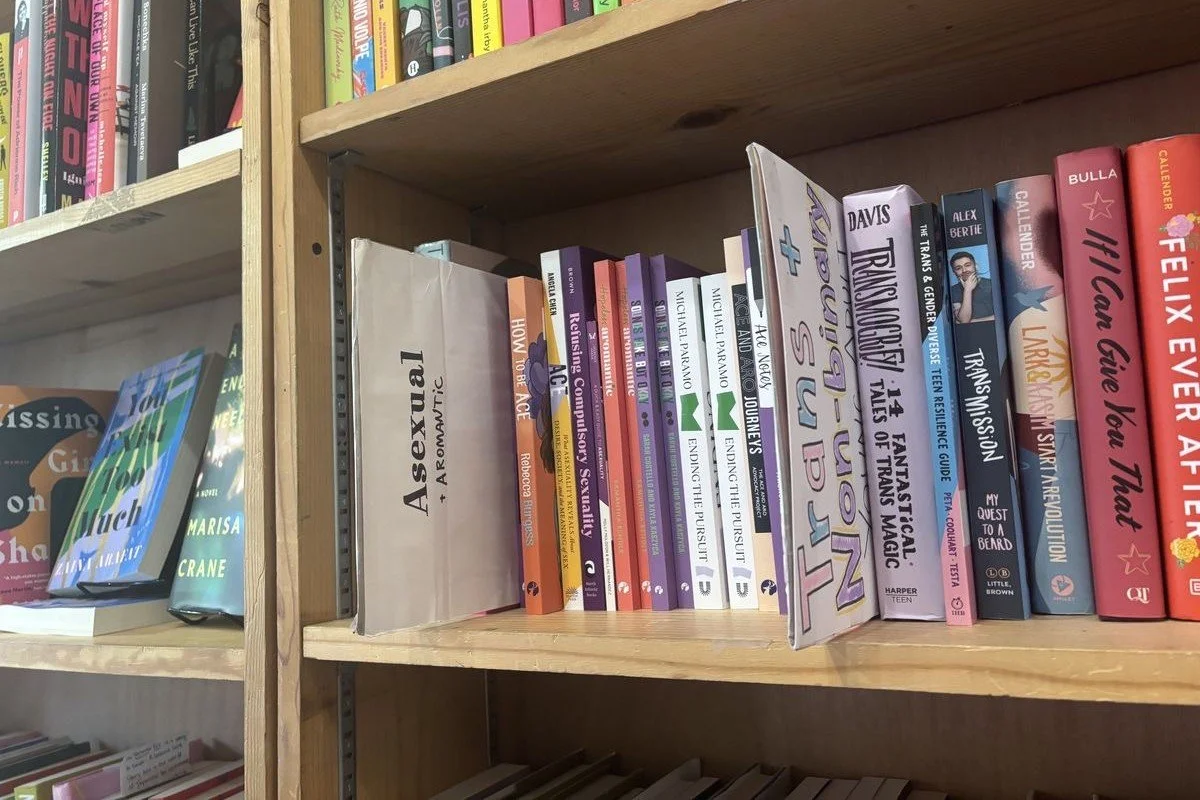

As an asexual, it’s been a long week. I’ve walked down to the Castro many times this past week, halfway through the trip, but one thing has stood out to me: WHERE IS THE ASEXUALITY? I get that a lot of San Francisco queer culture and life is based on the L and G, maybe sometimes the B and T, rarely ever the Q, but the IA+? Don’t even get me started.

I just wonder where the A could’ve gotten lost in this equation. I’ve seen rainbow flags, trans flags, bi flags, lesbian flags, labrys flags (another lesbian flag), kink flags, even Canadian rainbow flags and an Absolut vodka flag, but not once have I seen an asexual flag hung high and proud. Sometimes, if rarely, we’ll be on stickers and pins, always hanging in places that aren’t prominent or buried at the bottom of pin bins. I’m not saying I feel unwelcome, but I do feel something subtle… conditional inclusion. I could raise my hand and say, “I’m here!” and they would reply, “Indeed you are!” but if I don’t do that, I just become forgotten or melt into the background of everything. Yes, I feel like my authentic queer self here in San Francisco, and I even felt queer joy for the first time seeing some of my favorite drag queens (including Adore Delano!) live and jamming out with the rest of my community, but if you’re asexual, you’re invisible. So are so many other identities that are overlooked, despite being within the sea of smaller communities that make up a whole; they could make the community ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ, but it would still be A(B)CDEF(G)HIJK(L)MNOPQRS(T)UVWXYZ when it comes to representation.

I don’t blame the entire community for leaving us feeling invisible and unseen, I blame compulsory sexuality. If you don’t know what compulsory sexuality is, it’s similar to compulsory heterosexuality, just turn heterosexuality into sexuality. It’s the idea that all human beings are sexual beings and that is a core part of humanity (hint for you: it’s not).

At Frameline, I have seen movies upon movies that have contained interesting, happy, painful, free depictions of queer life. However, I have not witnessed a single plot in which the main role belongs to an asexual character. No, not one. People still do not think of us as worthy of having a story or being portrayed. And when representation is there, then it’s frequently flattened out into metaphor or ambiguity. We become the types who sit in the corner, late bloomers, shy, and the weird best friend who is never in a relationship. Once asexuality is mentioned, asexuality is said, not done. How, then, will other people learn how to identify us when we cannot name ourselves in public? I would be rambling for hours and hours, pages and pages if I started intersecting this with my other identities.

Where does this leave me? Still here, I suppose. I still walk through the Castro, digging around pins to find the lowly ace pin at the very bottom. I keep going to films hoping to see something with even a sliver of representation for the plethora of my identities, seeing things I’ve experienced on screen. But I think there’s one thing that the queer community needs to realize: we are not a monolith. Despite that, this is how our spaces sometimes work; the most powerful voices become dominant, the most already told stories become hegemonic, the most condoned forms of queerness. I know there is something better than that, though. In my opinion, we can have a broader movement. I think that the community, the one sustained by the hundred-year spine of resistance, the one that refused to assimilate, can also refuse to erase.

Not being attracted to anyone is not something that reduces my queerness. It queers me in a different way. And there is space for that. There must be. However, I do believe in something better. I do not think that we must be confined within our movement. But this is what I think, no, know: being asexual is one of the queerest things you can do. Not despite our differences, but because of our differences. Asexuality is not the toned-down version of queerness. It is not a step out of the conversation. It is a radical rethinking of it. We pose other questions. We oppose the notion that sex or desire must be at the center of identity. We oppose the supposition that intimacy should be romantic or physical. We take the framework of sexuality itself beyond itself, and what is queerer than that? Personally, I don’t think anything else is, but I know someone out there would argue with me about it. Queerness is about disrupting social norms around sexuality, romanticism, gender identity, and forms of intimacy, and yet people still think asexuals are just straight people in denial. But we’re not.

So no, my flag is not waving in the Castro. My story has not yet appeared on the Frameline screen. But I will continue to dream that there will come a day that queer spaces will be constructed with us in mind; not as an afterthought or a rainbow capitalist layer that must be fought through to the top. The day asexuality is no longer a cause of shame, but rather a cause of celebration.